In another post, we explored adding captions to Markdown. It is recommended that you read that post first in order to gather understanding about Markdown’s history and specifications.

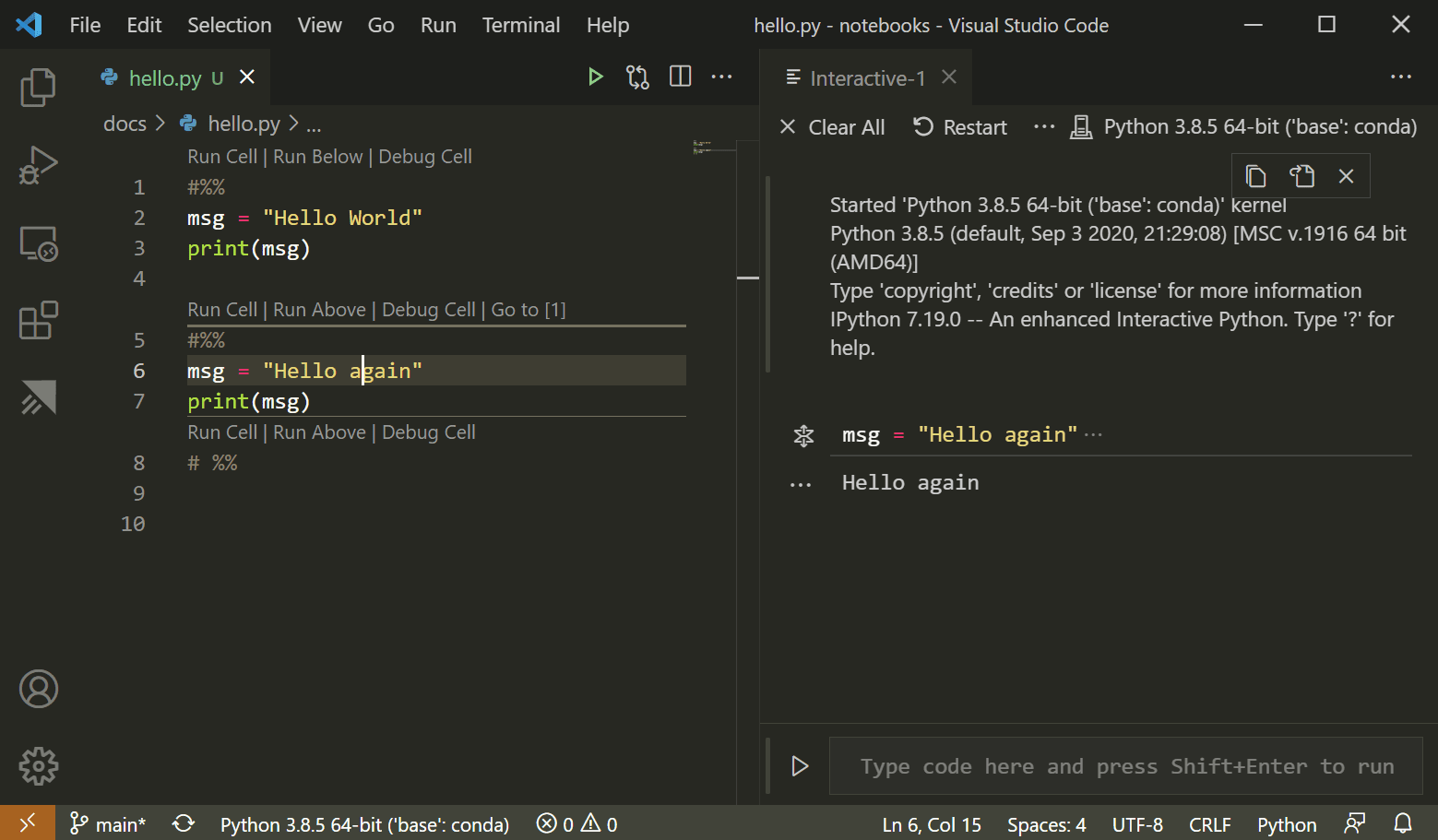

When writing Markdown, you may have come across situations in which it would be handy to add labels to your code blocks to give context.

Print DataFrame in Markdown-friendly format. New in version 1.0.0. Parameters buf str, Path or StringIO-like, optional, default None. Buffer to write to. If None, the output is returned as a string. Mode str, optional. Mode in which file is opened, “wt” by default. Python-Markdown ¶ This is a Python implementation of John Gruber’s Markdown. It is almost completely compliant with the reference implementation, though there are a few very minor differences. See John’s Syntax Documentation for the syntax rules. This is the personal website of a data scientist and machine learning enthusiast with a big passion for Python and open source. Born and raised in Germany, now living in East Lansing, Michigan.

For example, you may be discussing dropping code into certain files and what to have a label specifying where this block of code belongs, like in this DigitalOcean post. Or, you want the code language to be displayed in a label so readers can tell what it is, like in my post about the Vim thesaurus.

A code block label adds context to your code block so that readers understand where it goes, what it does, or a myriad of other things. Unfortunately, there is no native way of accomplishing this.

#The Info String

The line with the opening code fence may optionally contain some text following the code fence; this is trimmed of leading and trailing whitespace and called the info string.

The first word of the info string is typically used to specify the language of the code sample, and rendered in the class attribute of the code tag. However, this spec does not mandate any particular treatment of the info string.

–CommonMark specs

The info string immediately following the opening of a code block seems like the ideal place for such a label. CommonMark has discussed adding attribute syntax to the info string (among other Markdown elements) with a general syntax like this:

markdown

Although this syntax has been discussed for years, it has not been implemented into CommonMark. Some Markdown implementations allow syntax similar to the above, but with slight variations, so no syntax is very portable.

#Inline HTML

Sounding familiar? Once again, inline HTML comes to the rescue. A simple solution is to just create a label element above the code block, then style the label to your desire. For example:

markdown

Renders to:

test.md

markdown

In this way, we can specify code block labels with whatever content we want, be it a filename, language, or anything.

You may notice that most of the code blocks on this website have the language in them. I have written Javascript to do this automatically.

Storing user-created articles in your database as Markdown Syntax instead of the final rendered HTML solves so many problems. It’s not only more secure and helps you prevent XSS injections into your content, but it also makes it much more flexible to change the rendered version of the content at a later stage in the lifetime of your application.

This article that you’re reading right now has been written using Markdown Syntax. That’s how it’s being stored in the database, and then whenever you visit this page where the article is stored, Python code converts it into HTML and then add custom features such as classes, ids or other HTML attributes to selected elements, and then serves it to your browser.

This means that the creation of the content is strictly separated and decoupled from how it’s being rendered in its final form. Separating the logic related to the content in this manner brings many different benefits compared to creating the content using a WYSIWYG HTML Editor.

What’s Wrong with WYSIWYG HTML Editors?

For example, let’s say that we use a WYSIWYG HTML Editor to allow users to create their content. We then store this HTML in our database and serve it straight from the database whenever a user visits the page of the article. This setup means that we have to be concerned about the following things:

- Javascript injections into the content.

- A non-standardized look of articles and content.

- How the stored content will adapt to future changes to our design.

- Invalid HTML Markup.

What if we later realize that we want to modify the HTML of our articles? For example, let’s say that we want all <table> elements to have a certain class, or we want all links to be rel='nofollow', or we want all headlines to have an id attribute so that we can link to them?

We already stored the HTML and we are expecting to be able to use it straight from the database, so any kind of change or feature that we want to add that is related to our content would require us to write scripts or queries that updates the stored HTML from previous articles.

It quite quickly becomes tiresome and prone to mistakes and bugs, and it might lead to the developer avoiding updating older content, which in turn leads to our website having non-standardized formatting of the articles.

How to Use Markdown Syntax with Python

For most things you can think of, there is a python library available for it. So is naturally also the case for Markdown. There is a library called Python-Markdown that can easily be installed with pip using the following command:

Get weekly notifications of the latest blog posts with tips and learnings of how to become a better programmer.

No spam, no advertising, just content.

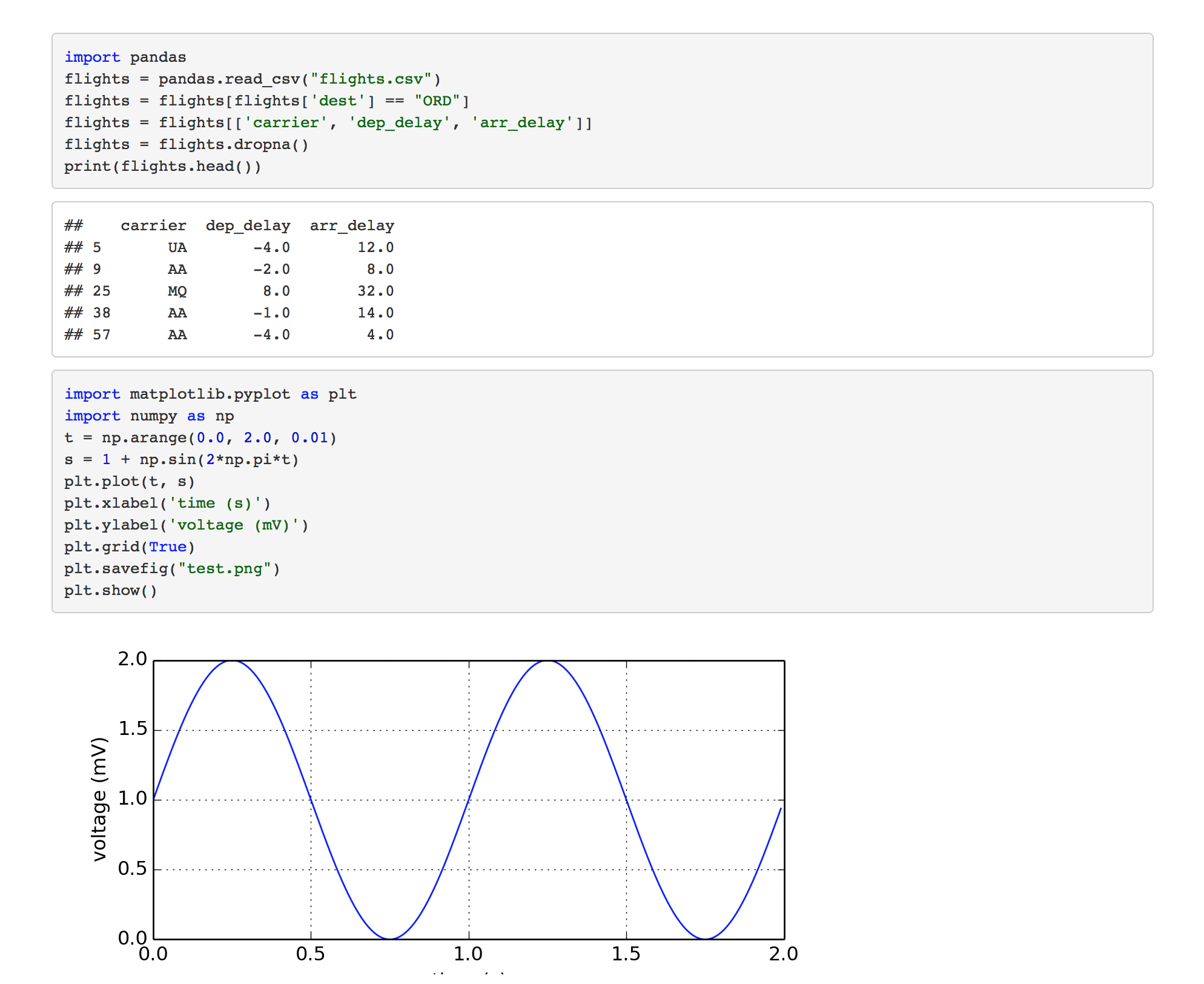

The library offers multiple useful methods and tools for when it comes to working with strings that are formatted using Markdown Syntax. For example, we can easily turn Markdown into HTML with a single method call.

The Markdown library also comes with the ability to add different types of extensions that modify the behavior or the way that markdown parse the Markdown Syntax. For example, you can modify how lists are parsed using the Sane Lists extension, or you can add code highlights of any <code> block using the CodeHilite extension.

Add Code Highlights using the CodeHilite Markdown Extension

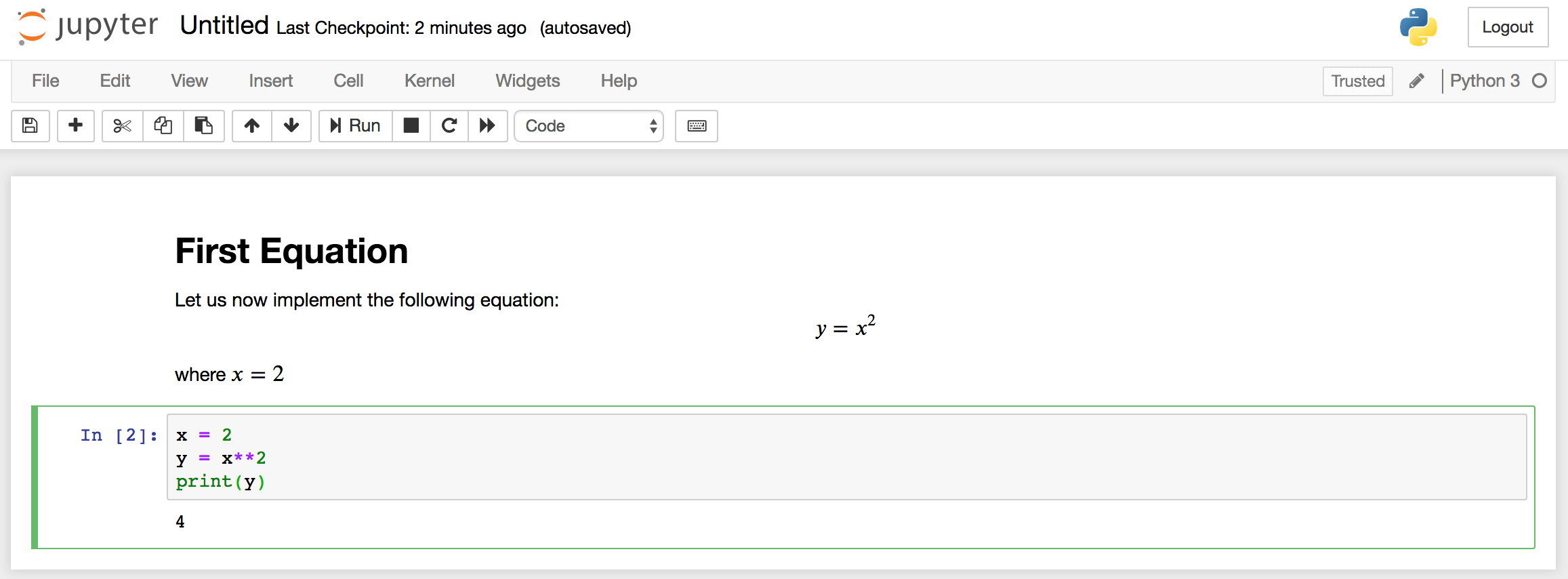

So let’s illustrate how you can activate an extension for the markdown library to modify the way it generates HTML out of your Markdown Syntax. In this case, we will add code highlights to <code> blocks that match the programming language that is being used.

If we don’t install any extension, code blocks are generated in the following manner:

Gets rendered as:

So technically, it works. It does understand that it is a code block and it wraps it as a <code> element. But what if we want to add highlights so that different syntax is colored in different colors, to improve the readability for the visitors that come to read our articles?

We might want to wrap the print( part with a <span> to make it red, and then wrap the string within with a <span> that turn it into a green color. It would be a mess to attempt to do all of this by hand, and this is exactly the kind of things that the “CodeHilite” extension does for us.

To be able to enable the extension, we first have to install its dependency Pygments. Pygments is a popular syntax highlighter written in python and it is what takes care of the bulk of the work that the CodeHilite extension does. We can install it using pip.

To enable the CodeHilite extension, all we have to do is to add the extensions kwarg to our markdown() call that turn our Markdown Syntax into HTML.

This then wraps our code into the following HTML syntax:

But obviously, just wrapping things in <span> elements doesn’t do much. What does class='k' or class='p' even mean? Where are those styles defined? Well for this we have to import a CSS stylesheet that defines all of the style rules required.

To do this, we can either generate our own styles which are documented in the CodeHilite Documentation by using the following command:

The command will generate a styles.css file for us that is populated with style rules that expect the code highlighting to be wrapped in a container with the .codehilite class.

The other alternative is to check out GitHub user richleland who have created multiple presets that follow common IDE styles that we can use.

How to Modify Markdown’s Generated HTML with BeautifulSoup

So now we have installed the markdown library and we’ve learned how to add extensions that modify some of the generated HTML. But what if we also want to add our own custom attribute to different HTML elements?

For example, right now a user can create an HTML link using the Markdown Syntax. By default the HTML element is just a pure <a> element. But what if we want to add rel='nofollow' or target='_blank' to each link?

Python Print Markdown

Well, we could create a Markdown Extension to achieve this, but we can also use something like BeautifulSoup4 to parse and modify the HTML that has been generated before we serve it to the user. This gives us a lot of choices and possibilities to add anything we’d like to our final output.

Install BeautifulSoup4

BeautifulSoup4 is a super popular library that gives the developer an amazing set of tools to easily parse and modify HTML. It’s both being used by web crawlers to understand contents of websites, but it can also be used by us to read and modify HTML elements on the fly before it’s served to our users.

We can install BeautifulSoup4 using pip.

We are then ready to use it in our code by importing it as:

Use BeautifulSoup to Modify HTML In-Place

So let’s take the example that we used in the section above regarding modifying <a> elements and add things such as target='_blank' or rel='nofollow' attributes to it.

Here’s an example of how this could be achieved:

This will then do the following things:

- Use the

markdownlibrary to turn our Markdown Syntax to HTML. - Use the

codehiliteextension to add Code highlights to any code blocks. - Turn the HTML into a

BeautifulSoupobject that allows us to easily search and iterate through it. - Add

relandtargetattributes to all HTML<a>elements. This all happens in-place. - Finally turn the

BeautifulSoupobject into HTML and return it.

It’s easy to imagine a lot of other things you can achieve with this combination of tools such as:

- Make all images responsive by adding

img-fluidBoostrap classes to them. - Add title and alt tags to images and links to improve On-Page SEO.

- Treat internal links and external links differently and set different

relvalues depending on where they link. - Add

idto elements so that they can be anchored and linked to.

Benefits and Conclusion of Markdown Syntax over HTML WYSIWYG

This style of working and storing content is the way that this website stores and manage the content of all articles. It has many different benefits over the traditional WYSIWYG method where you store the final HTML ready to be served.

- We have more control of the HTML that we output since we process it before rendering it. It’s not completely in the hands of the users.

- Users can focus more on the content they produce, than how it is supposed to look like in its final form.

- Since we never allow users to input raw HTML, we can treat it all as unsafe and completely prevent things like Javascript injections.

- All of our articles will always look the same and follow the same style guides. We will never have an article that has a different font size on one of their headlines than another.

Some people argue that Markdown Syntax is more difficult to learn than using WYSIWYG HTML Editors. This is simply not true. First of all, you can use editors for Markdown Syntax as well that allow you to have shortcuts to do things like bold text, add links or upload images.

Second of all, Markdown Syntax is no doubt simpler than HTML and XML.

Python Pretty Print Markdown

Get weekly notifications of the latest blog posts with tips and learnings of how to become a better programmer.

Python Markdown Pdf

No spam, no advertising, just content.